Ben Graham’s net-net strategy

A historical curiosity or a workable strategy today?

“Our net-net stocks strategy gave such good results for us over a forty-year period of decision making that we eventually renounced all other common-stock choices based on the regular common stock procedures, and concentrated on these ‘sub-asset stocks." Ben Graham

Benjamin Graham was the pioneer of value investing. The common view of this school is it looks for cheap or bargain stocks. This might involve metrics such low Price /Earnings Ratios or Price to Book Value Ratios. Graham preferred a simple and workable formula based on the balance sheet. This is commonly known as the net-net Criteria. Graham had lost money in the great crash of 1929 and was subsequently looking for extremely conservative strategies.

Graham determined his criteria by looking at current (or short-term) assets such as cash, short-term investments, receivables and inventories. These are liquid assets which can normally be turned into cash quickly.

Graham elected only looked at those companies where total current assets were greater than all non-equity liabilities. In other words, current assets are so high, they were greater than all the money the company owes (whether short- term or long term) to all parties (suppliers, banks etc) except equity holders.

Graham was looking for positive Net Current Assets (NCA)

Where NCA = Total Current Assets minus all non-equity liabilities.

This is a tough criterion. Normally investors, concerned about liquidity check whether current assets are greater than current liabilities. Are assets easily convertible to cash (say within 12 months) greater than liabilities which will need to be paid in the next twelve months.

Graham goes beyond this and requires current assets be enough to pay off not just short-term liabilities but long-term liabilities such as debt and preferred shares as well. This is a demanding criteria and only a small proportion of quoted companies will meet it at any point of time.

Positive NCA was not conservative enough for Graham. He added another margin of safety. This second requirement was that the market capitalisation of the company should be 66% or less than the NCA. In other words, Graham was looking at a minimum 33% discount to NCA. This implies a huge margin of safety.

This in summary is Graham’s net-net approach.

Net-net ignores the earning power of the company as it does not consider the P/L of the company. It ignores what accountants’ term “going concern” and considers the company as if it was “dead”. It is the perspective of a company undertaker or liquidator.

Suppose a company has an NCA of US100 per share but is trading at a price of US$ 60 per share. This satisfies Graham net-net criteria as

1. The NCA is positive (+$100)

2. The share price is at more than 33% discount to the NVA

A theoretical corporate undertaker or liquidator could, in principle, try to buy the company at $60. She could then monetise all the current assets and pay off all liabilities and in theory have $100 per share in cash and realise a profit of $ 40 per share. Slippage might mean only $90 is realised but that is still a good profit because of low entry price.

Warren Buffet called this cigar butt investing. It is the equivalent of finding a discarded but smoking cigar butt on the floor and getting a could of puffs on it. It was not a great smoke, but it was free. It is an investment philosophy that appeals to the cheapskate or tightwad.

Graham’s theory was a net net company was trading so cheaply that it was statistically likely to recover and trade up towards the NCA value. In the theoretical example above, the share bought at $60 per share could be sold if it traded up to $90 for a 50% gain.

Graham followed this strategy and his investment analysts (who included Walter Schloss and Warren Buffett) worked with him. They scoured the Moody’s Manuals (which had one page financial summaries of thousands of companies) to identify the most promising net-net stocks. Buffet’s job was to highlight these to Graham. It must have been a frustrating existence as Graham usually had a reason for rejecting most of them.

The net net investor does not need detailed knowledge about the company’s business. There is no need to meet management or do detailed further research. As Graham did not know which companies would recover or how long it would take, he further reduced risk by allocating only a small percentage of his portfolio to each chosen company. This high level of diversification added a further element of conservatism in the strategy.

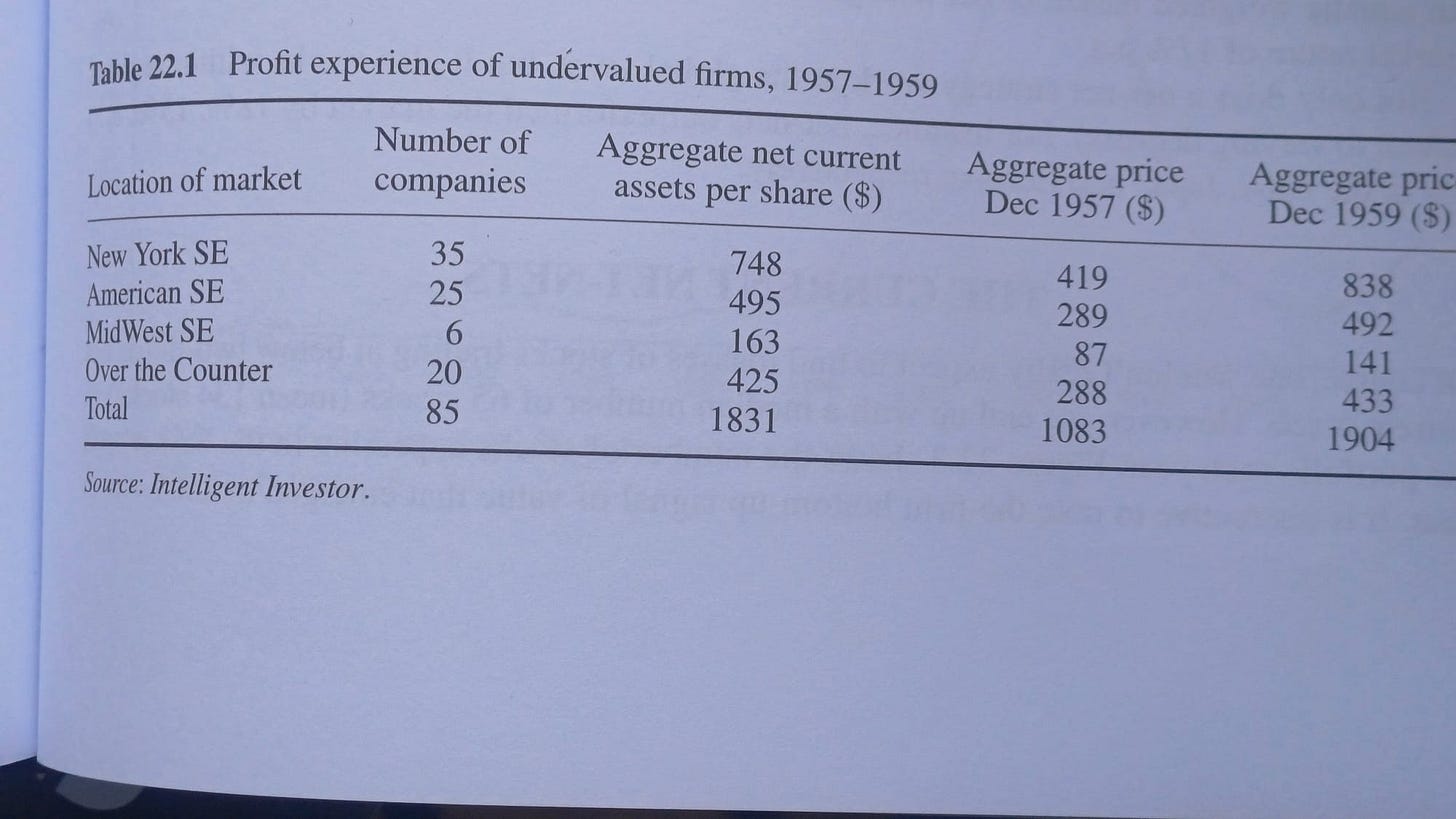

In his book, “The Intelligent Investor”, Graham showed some data about the performance of the net-net Strategy where stocks were identified in December 1957 and sold in December 1959. The performance was quite good.

Graham notes “The gain from the entire “portfolio” in that period was 75% against 50% for the Standard and Poor’s 425 Industrials. What is more remarkable is that none of the issues showed significant losses, seven held about even, and 78 showed appreciable gains.”

In 1986, Henry Oppenheimer published a paper in the Financial Analysts Journal examining the returns on buying stocks at or below 66% of their net current assets value during the period 1970-1983. The holding period was 12 months.

The number of stocks that met the net net criteria varied greatly. Over its life, the portfolio contained a minimum of 18 stocks and a maximum of 89 stocks. The mean return from the strategy was 29% p.a. against a market return of 11.5% p.a.

The investment strategist, James Montier tested a net-net strategy for developed markets for the period 1985- 2007. He reported that an equally weighted basket of net-nets generated an average return above 35% p.a. versus a market return of 17% p.a. The strategy outperformed the market by 18%, 15% and 6% in the USA, Japan and Europe respectively. So Montier’s work indicated that such a strategy could produce market beating returns in many developed markets.

Montier observed that few stocks met the strict criteria. The median number of qualifying stocks was 65. In 2003, the number short up to over 600 stocks. We note in passing that in March 2003, the stock market bottomed after the great dot.com crash and rallied for 5 years,

Academic studies suggest that net-net is a winning strategy. However, it is not widely followed. There are a few possible reasons for this.

Net-net companies are much more risky than the average stock. We have to clarify what we mean by risk. Standard academic models such as the CAPM model pioneered by Harry Markowitz define risk as the short-term price movements in stock prices, captured in statistical measures such as volatility and variance. For value investors, it makes no sense to measure risk as short-term price movements. The real measure of risk for them is the probability of permanent loss of capital. Montier defined permanent loss of capital as a decline of 90% or more in a single year. He noted that 5% of net nets suffered such a permanent loss of capital compared with 2% in the broader market.

Behavioural economics shows that people generally are loss averse: a 10% loss causes much more distress than the satisfaction from a 10% gain. In addition, investor often look at the performance of individual stocks as much as the performance of the overall portfolio. This is known as narrow framing. Narrow framers will avoid as net-net as it gives rise to more permanent losses at the stock level than a conventional broad market strategy. This is even though at the portfolio level, the net-net is quite likely to outperform a conventional strategy

Net-net essentially requires stocks to be trading at extremely cheap levels. This implies small caps and/or stocks about which there is a lot of bad news or sentiment. Many net-net stocks will be those which the market believes are likely to go bust. Montier found the median market cap of the net-net was just US$ 21mn (average was $121mn).

In short it will be an “ugly” looking, unconventional portfolio, which most investors will instinctively recoil from.

Graham was investing in the 1950s and early 1960s. Memories of the great crash of 1929 and the depression of the 1930s was still fresh in the public mind. As a result, stocks were viewed as very risky and traded at lower valuations relative to fundamentals and the levels they would reach later.

Warren Buffett followed the Graham strategy successfully until the late 1960s. However, towards the end he found that the strategy did not work as well as before. He announced he was winding up the Buffet partnerships in 1969 and returned money back to investors. Some of this in the form of Berkshire Hathaway shares.

I believe this can be explained by two factors. First Buffet’s success meant that he was handling ever larger sums of cash. Net-net identifies very small companies and Buffett found it increasingly difficult to deploy capital. By the late 1960s, the memories of the 1929 crash were fading and a new investor base was coming in and it was era of the go-go nifty 50. Valuations had moved higher. There were fewer and fewer cigar butts.

Extract from Warren Buffet’s last Partnership letter. In 1969, he only made 7% but still beat the Dow which fell 18%. He was increasing finding it difficult to match his overall returns. (29.5% CAGR for 13 years)

In a 1993 talk at Columbia University Buffett described some the cigar butts he found in the 1950s :

“I found the Union Street Railway, in New Bedford, a bus company. At that time, it was selling at about $45 and, as I remember, had $120 a share in cash and no liabilities.”

Buffet changed his investment philosophy over time under the influence of Charlie Munger and Phillip Fisher. Walter Schloss who managed much smaller sums of money carried on in the original Graham net-net spirit in a six-decade long investment career.

Warrant Buffett once said this about Walter Schloss

“Walter has diversified enormously, owning well over 100 stocks currently. He knows how to identify securities that sell at considerably less than their value to a private owner. And that's all he does...He simply says, if a business is worth a dollar and I can buy it for 40 cents, something good may happen to me. And he does it over and over and over again. He owns many more stocks than I do -- and is far less interested in the underlying nature of the business; I don't seem to have very much influence on Walter. That's one of his strengths; no one has much influence on him.”

Buffett later continued with the following...

”Following a strategy that involved no real risk – defined as permanent loss of capital – Walter produced results over his 47 partnership years that dramatically surpassed those of the S&P 500...There is simply no possibility that what Walter achieved over 47 years was due to chance.

I first publicly discussed Walter's remarkable record in 1984. At that time "efficient market theory" (EMT) was the centerpiece of investment instruction at most major business schools. This theory, as then most commonly taught, held that the price of any stock at any moment is not demonstrably mispriced, which means that no investor can be expected to overperform the stock market averages using only publicly-available information (though some will do so by luck). When I talked about Walter 23 years ago, his record forcefully contradicted this dogma

We reported on Walter Schloss’s investment philosophy and that note can be found here.

It is sometimes believed that net-net is a historical curiosity which can only works in times (like the 1950s) when people are scared of stocks or there are too many stocks and too few analysts following them.

This is different from today when we have a global equity cult, everybody has instant access to company financials there are hundreds of thousands of equity analysts following stocks. Surely, today with all these there will be no extreme statistical bargains.

Warren Buffett gradually steered away from classic Graham because of the size of the money he was managing. The value of the partnerships capital was over $100mn. Buffett was once asked what he would do if he was investing small amounts of money. His answer was intriguing.

Yeah, if I were working with small sums, I certainly would be much more inclined to look among what you might call classic Graham stocks, very low PEs and maybe below working capital and all that. Although -- and incidentally I would do far better percentage wise if I were working with small sums -- there are just way more opportunities. If you're working with a small sum you have thousands and thousands of potential opportunities and when we work with large sums, we just -- we have relatively few possibilities in the investment world which can make a real difference in our net worth. So, you have a huge advantage over me if you're working with very little money."

This raises the question of whether a net-net strategy would work today. The Montier study and Walter Schloss’s track record suggest this could be the case. We will investigate this further and report on it here.

Net-net investing is the process of buying a company’s common

shares below a conservative estimate of the firm’s per-share

liquidation value. Assessing a company’s liquidation value in a

conservative manner and then buying its common stock at or below

that value is the essence of net-net invest -Ewen Bleaker

“It always seemed, and still seems, ridiculously simple to say

that if one can acquire a diversified group of common stocks

at a price less than the applicable net current assets alone –

after deducting all prior claims, and counting as zero the fixed

and other assets – the results should be quite satisfactory.

They were so, in our experience, for more than 30 years. - Ben Graham