AI has been one of the main reasons for the US stock market momentum in the last 18 months.

Michael Cembalest, at JPMorgan, recently observed “AI related stocks have accounted for 75% of S&P 500 returns, 80% of earnings growth, and 90% of capital spending growth since ChatGPT launched.”

The markets advanced strongly in October 2025, and indices hit new highs. The market capitalisation of Nvidia, the world’s most valuable company hit $4.6trn, 20% larger than the entire stock market of the UK or India.

There are many articles arguing there is a bubble in AI stocks. Is this the case?

This is an important but difficult to answer question.

A quick AI search yielded the following definition of a bubble. It was as follows:

A stock market bubble is a rapid and unsustainable surge in stock prices far above their intrinsic value, driven by speculation and herd behaviour rather than fundamental business performance.

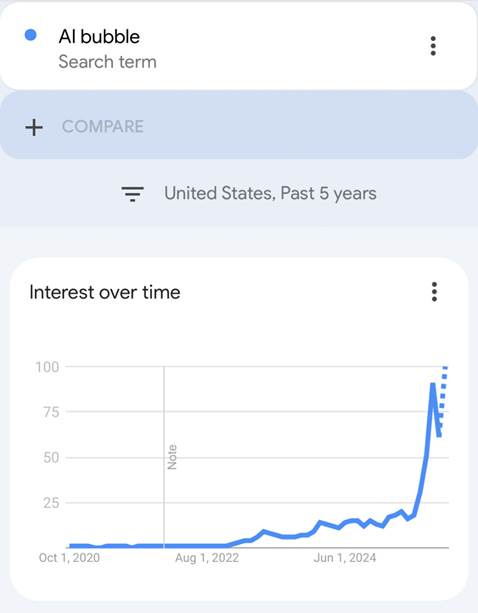

Searches for the term AI bubble are at a five- year high and is likely to be an all-time high.

Many asset prices are above what the fundamentals might indicate to be their fair value. It is not limited to stocks. We have seen huge increases in the prices of precious metals, cryptocurrencies, bonds as well as many stocks in the last five years and in 2025.

It is quite difficult to find assets which are trading at meaningful discounts to their fair values. In our daily work, we struggle to find cheap stocks in the US, irrespective of industry sectors.

Warren Buffett has a record cash pile of over $340bn (30% of total assets) as he can’t find anything cheap enough to buy in his (highly limited) investment universe.

Bonds are very expensive. US inflation is close to 3%. Who is buying 10- year Treasury Bonds at a yield of 4.10%. Yield spreads of risky bonds are at record lows relative to the already expensive Treasury Bonds.

You can only have a bubble where there are readily available prices. In the last decade much investment has flowed into private markets which has no readily available prices. Billions of dollars have been invested in private equity, private credit and many other obscure and opaque structures. There are no prices so valuations are based on “models” or are just guesses, or the product of wishful thinking. Buyers are scarce on the ground and there are few exits.

We would guess that most private assets are greatly overvalued and are probably in a bubble, but given the absence of market prices, it is ascertain this.

Given the current environment, AI stocks are likely to overvalued but are they in the bubble?

Perhaps some of them are. Take OpenAI – it completed a deal to help employees sell shares in the company at a $500bn valuation. Is it worth that much?

It has 700mn weekly active users across its platforms but most of them are not paying anything. OpenAI, by its own statements, is not expected to be cash flow positive or profitable until 2029. It is currently burning through a lot of cash. In the first six months of 2025, the company had revenue of approximately $4.3bn and an operating loss of $2.5bn. This was driven by $6.7bn spent on R&D.

The epicentre of the AI universe is Jensen Huang and Nvidia. If there is an AI bubble, that is good place to look.

As is well known, Nvidia started off as a designer of GPU’s aimed at gamers. Later, their products found favour with Cryptocurrency miners. As the latter faded, Nvidia saw demand from AI datacentres. The release of Chat GPT 3.5 in November 2002 triggered a huge arms race for AI datacentres for both training AI models

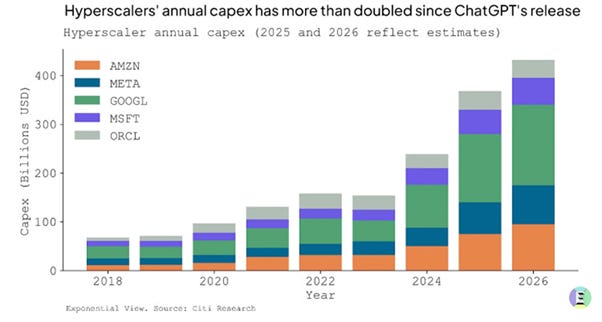

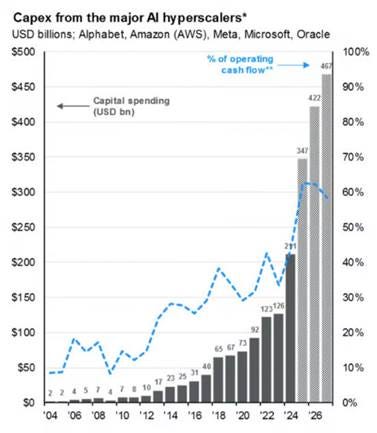

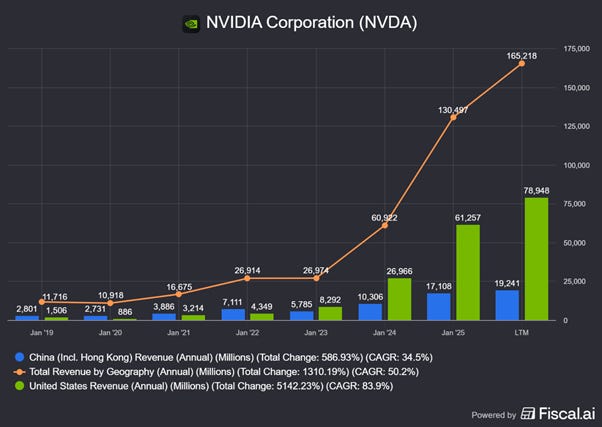

Tech companies are projected to spend about $400bnthis year on infrastructure to train and operate AI models. These are huge numbers, and they are expected to grow in the next few years. Most of this is for AI datacentre investment and a lot of will be spent on Nvidia chips, software and networking services.

However, by 2027, the capital expenditure of the big five hyperscalers is expected to be cost 100% of operating cashflows (See chart below). Any increases beyond will have to be financed by debt, equity or funding from other external parties such as PE giants.

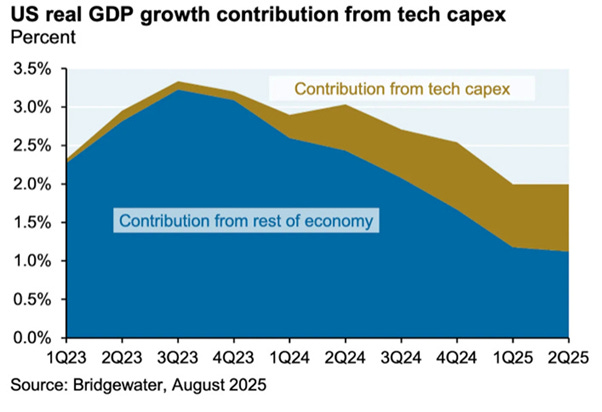

Datacentre related spending probably accounted for half of GDP growth in the first half of the year.

Some of this goes into land or buildings but an estimated 35% to 40% is for GPUs, GPU software and networking. Nvidia has a near 90% market shares in datacentre GPUs and so is seeing overwhelming demand.

Generative AI effectively requires Nvidia GPUs, as it’s almost the only company making the high-powered GPU needed. Nvidia also has CUDA — a deep collection of software tools that lets programmers write software that runs on Nvidia GPUs.

Nvidia’s enterprise-focused GPUs like the A100, H100, H200, and more recently the Blackwell-series B200 and GB200 (which combines two GPUs with an NVIDIA CPU) are in short supply

These GPUs cost anywhere from $30,000 to $50,000 (or as high as $70,000 for the newer Blackwell GPUs). A state-of-the-art datacentre might have a 100,000 of them. This might cost $4-$5bn for GPUs alone. Each GW of AI computing capacity costs about $50bn to deploy. OpenAI has done deals which would give it access to up to 20GW of compute capacity which would be $ 1trn (!).

Look at things from the perspective of Jensen Huang, the CEO of Nvidia. You have been running your company for two and a half decades, when almost overnight, some of the largest, most cash- rich companies on the planet are demanding to buy as much product as you can supply. What do you do?

You make hay while the sun shines. You use the money to invest in an aggressive 12–18-month product development cycle which leaves the competition (such as it is) struggling to keep up.

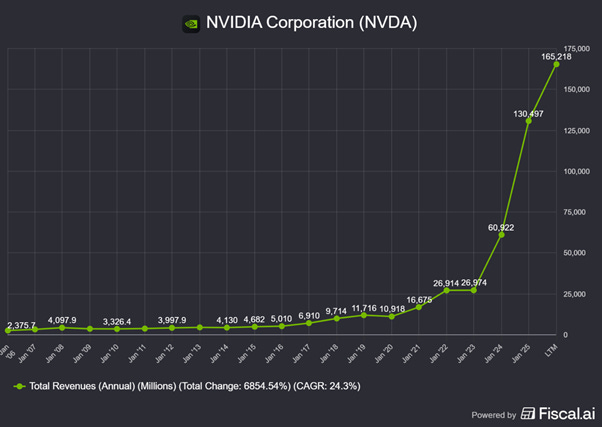

Your revenues and cash flow go through the roof, and your stock price follows.

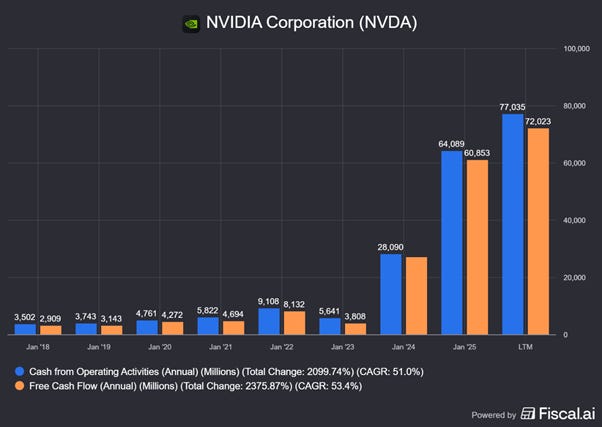

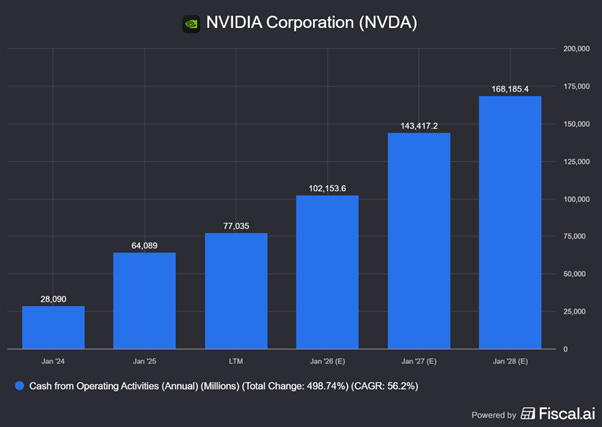

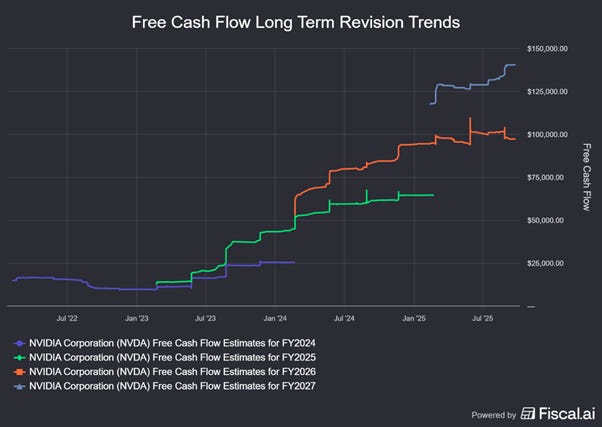

The annual free cash flow is now $65bn and it is expected to hit $168bn by 2028.

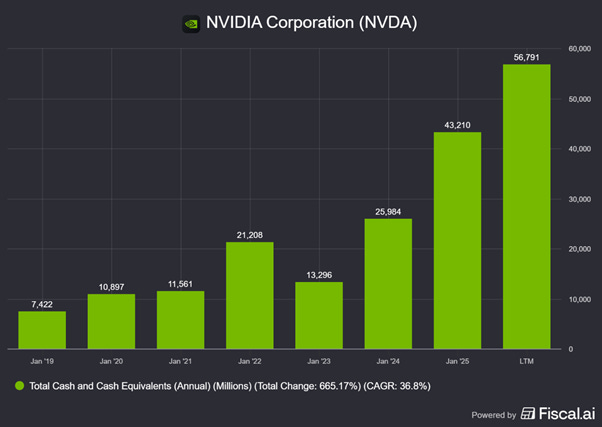

The cash pile has grown to $56bn and your long-term debt is just $8bn.

In short, Nvidia is in a very strong position. The only blemish is China. It is home to the largest number of AI researchers and should be close second (to the US) in terms of sales. However, the US government bans you from selling the most advanced chips and brings in more restrictions and in response the Chinese government asks their companies not to buy US chips.

What do you do?

You go to the only people who have even more money than the large tech companies, namely countries. You persuade them that it is strategically important for them to establish Sovereign AI. They need datacentres on their own soil as they can’t fall behind in the AI race or let their national data be stored outside.

The effort is remarkably successful. Jensen Huang has hosted AI summits with world leaders in London, Paris, Abu Dhabi and elsewhere.

Government decision making is slower than incorporates. However, they commit to invest within two years. This is ok since you currently do not have the product to supply them anyway. You ask Taiwan Semiconductor to expand production capacity to meet the pipeline of huge sovereign demand sure to come in two years’ time.

Currently Meta, Microsoft, Amazon, Google and Oracle plus a couple of others make up 42% of Nvidia’s revenues.

Microsoft, Amazon and Google have huge cloud hosting businesses, where they hold client data. They now want to provide access to AI LLMs at scale to their corporate client base.

A few large companies such as Meta, OpenAI and Anthropic which need access to GPUs and datacentres to train their models. Thousands of others need access to cloud based GPUs for model inference, to use LLMs at scale to process their workflows.

This has driven the hyperscaler demand for datacentres and GPUs.

Nvidia’s success has been as the classic seller of shovels in a gold rush. This refers to Cecil Rhodes who made his fortune in the South African Gold rush by selling shovels and supplies to the miners who flooded into the Goldfields rather than venturing on a prospecting expedition himself.

However, recently Nvidia has changed this strategy a little, by investing in neoclouds. These are companies set up to buy Nvidia GPUs build out datacentres and rent out the capacity for which there is huge demand.

Nvidia has invested in neoclouds such as CoreWeave, Nebius and Lambda. It also plans to invest $ 500mn in Nscale a UK-based neocloud.

Neoclouds exist only to provide access to GPUs for AI. This contrasts with the cloud hyperscalers which have huge non-AI businesses.

Neoclouds typically have significant debt (building datacentres and equipping them is expensive) but are big buyers of the GPUs, CUDA and networking services that Nvidia provides.

The neoclouds need to raise billions in debt. To raise this, they collateralize the GPUs they have, along with contracts from customers, which they use to buy more GPUs.

CoreWeave has equity of $1.3bn and totals liabilities of $17.8Bn. In other words, it is highly leveraged. Nvidia has small amount of the equity in Coreweave but has got large orders from Coreweave thanks to the deployment of the leveraged capital.

Let us look at some illustrative numbers. Suppose 50% of the $18bn are invested in products and services of Nvidia. That translates to demand of $9bn. Given Nvidia operating margin of 60%, this will be operating profit of $5.4bn and likely free cash flow of about $4.3bn. Nvidia’s equity investment in Coreweave is $3bn. This is a good deal for Nvidia. It gets 140% of its investment back after two years and still has the shares in Coreweave (which have soared).

Nvidia currently has similar deals with Lambda which plans to list next year and Nebius which is already listed.

Nvidia’s exposure is limited to its stake, but its sales can be multiple of this thanks to leverage at the neocloud entity level.

In the last few days Nebius (NBIS) has announced a deal with Microsoft worth $17.4bn over five years. This was quickly followed up by a second deal which gives Microsoft access to 100,000 plus of Nvidia’s newest GB300 chips.

Microsoft has committed over $33bn to similar neocloud agreements with CoreWeave, Nscale, and Lambda.

CoreWeave has said it is in advanced talks with Google where the latter will rent Nvidia Blackwell chips.

Neoclouds may prove to be poor equity investments but investing in them still makes sense for Nvidia. Their purchases of Nvidia equipment and service will be much more than the amount invested.

Renting GPUs is a good option for hyperscalers such as Microsoft and Google as they do not require the upfront capital outlay ownership would require.

The Nebius’ deal with Microsoft included a clause that Microsoft can terminate the deal in the event the capacity isn’t built by the delivery dates. Nebius has already used the Microsoft contract to raise $3bn to build the datacentre required.

These neocloud deals are relatively small commitments for Nvidia. The neocloud deals are small compared to Nvidia’s cash resources and current and prospective cash flows. However, by funding their customers to a limited degree, they are departing from the pure shovel supplier model

The market was worried and surprised two weeks ago, when Nvidia announced it was going to invest up to $100bn in OpenAI to deploy up to 10 gigawatts of AI infrastructure.

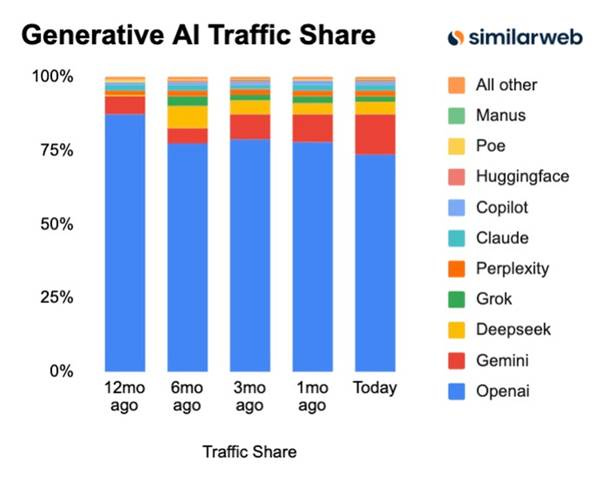

OpenAI have 700mn users and are the undisputed market leaders in GenAI traffic (see chart below).

However, servicing the requirements of this huge base of users requires huge AI infrastructure which is well beyond the financing capacity of OpenAI.

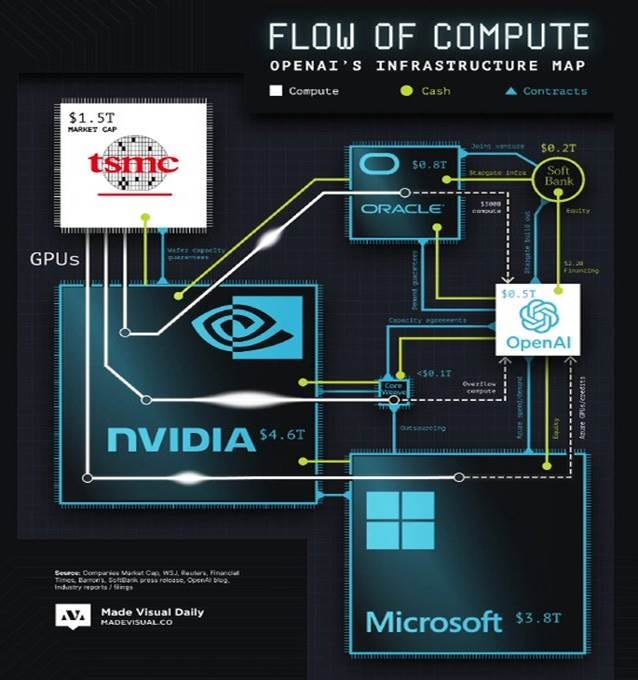

As is well known, OpenAI has a hybrid structure. They started off as a non-profit but later added a for-profit arm. Microsoft invested $20bn in the latter in stages. Not all the investment was paid for in cash. Some of it was in credits which could be redeemed with the utilisation of Microsoft’s Azure cloud platform. It was a very good deal for Microsoft but as OpenAI has grown it looks a poor deal for them. The two parties have been negotiating to amend the deal, but Microsoft has been dragging their feet keen to extract their pound of flesh

OpenAI has huge requirement for compute Infrastructure. Microsoft has been investing heavily along the other large scale hyperscalers. Microsoft has huge needs for compute for its own needs (GitHub, Copilot etc) and demand from other customers. So Open AI lacks cash and compute infrastructure

OpenAI are competing with LLMs from Google, Meta, and Amazon, companies which have huge existing businesses which generate large cash flows which can be used to fund AI investments. OpenAI is burning cash despite achieving a scarcely believable $500bn valuation. It is set to lose $10bn this year.

How to Square the circle?

One part of the answer, at least in the medium term, might be the Stargate Partnership. Sam Altman has used his political connections to rope in the US government along with Oracle in this project.

Oracle will build and operate large data centres in Texas and later in New Mexico). The final capacity will be a incredibly huge 10GW of compute. This will take time. As we have noted in previous notes on Oracle. Oracle does not have the money. It has very large debts and after a recent large $26bn debt issue is unlikely to be able to borrow more without a credit downgrade.

A dilutive equity issue many be inevitable if they are to stay in the AI race.

OpenAI has signed an eye-popping $300 billion, five-year, cloud computing agreement set to begin in 2027 with Oracle Cloud Infrastructure (OCI). That is all fine and dandy but neither Oracle nor Open AI has the money.

OpenAI secured $4bn in bank debt last year and raised about $47bn from Venture Capital deals in the past twelve months. It is not enough: it needs a lot more.

Nvidia has some $50bn in cash and is predicted to generate much more every year. Nvidia has promised to invest up to $100bn in OpenAI. If this is spread over five years beginning (say) 2026, it is about $20bn a year. This is large sum of money but can be financed from the Free Cash Flow analysts expect Nvidia can generate in the just the next three years. (See chart below).

As seen in the CoreWeave above, the equity in OpenAI can be leveraged at least three times. Nvidia’s $100bn investment is likely to lead to orders of a much greater magnitude than the investment in about two to three years. The payback for the investment is three years, and they will retain OpenAI equity optionality.

As we have noted before there is some circularity in the money flows. Nvidia will finance OpenAI equity), which will then fund Oracle (loan?) which will then purchase from Nvidia.

The announcement of this deal led to many comments that this was vendor financing like the 2000 TMT boom when companies like Lucent Technologies and Cisco spent hundreds of millions of dollars financing their customers. The latter went bust and the former faced bad debts and a collapse in their share price. The critics may be right: financing your customer is never a good idea.

However, this not the same situation as 2000. Nvidia’s largest customers, the large tech hyperscalers, are profitable and cash flow positive. They do not need financing by Nvidia. However, their investing plans are close to the limit of their ability to finance from internal cashflow. They can get external financing from the bond markets, banks or infrastructure investors such as Blackstone who are investing in datacentre assets.

Nvidia is no longer the neutral shovel seller but a (small) investor in a subsection of their customer base. Their investment can be leveraged and Nvidia is likely to recover their investment within three years while retaining equity upside as long as the demand for AI continues to be strong. This is the key assumption.

Nvidia is generating a lot of cashflow riding the AI boom. As an investor I do not want them to return cash to me but to invest in the AI ecosystem. In many ways they are extremely well placed to do so successfully. A $10 trillion Market cap will not be achieved without taking some risks. One commentator suggested NVIDIA has moved “from arms dealer to kingmaker.”

Commentators are worried that a large part of the capital investment will be misallocated as they will create infrastructure for which there is no demand.

They have mental models of the railroad boom which created the modern America, the cable boom of the 1980s or the TMT boom of the late 1990s. In each case, the enterprises that funded the early infrastructure burned their capital and collapsed before seeing returns. The real winners were often those who came later, building on the infrastructure that other had created.

It is too early to say who the winners of the AI boom are. However, Nvidia, which has risen 1370% in the last three years, is already a winner. It has probably picked up all the low hanging fruit. There are a number of factors which could lead to slower demand growth for Nvidia going forward.

The hyperscalers are looking to reduce their dependence on Nvidia and are developing their own AI chips (custom silicon) such as Amazon’s Trainium or Google TPUs.

AMD is likely to provide greater competition to Nvidia GPUs.

Chinese companies like Huawei, SMCI and others are likely to develop much better GPUs and software which will compete with Nvidia in China and globally.

Nevertheless, Nvidia is likely to do well as long demand for AI compute and therefore its products and services continues to grow. There is a good chance that sovereign AI demand is likely to pick up strongly in two years’ time.

However, even if demand grows, it’s not clear supply will grow in line. There are several possible supply constraints. AI datacentres need capital land, power, buildings. Servers, GPUs, CPUs Memory chips and data storage devices.

A shortage of some or all of these could act as major supply constraints. There are issues about where the money will come from. The prices of memory chips and storage devices have been rising in 2025. Land acquisition is also becoming an issue as people do not want giant datacentres in their neighbourhoods. However, the biggest constraints is likely to be power as AI is very power intensive.

Power companies in the US are overwhelmed with the sudden growth in demand. The grid operators and power companies had got used to 1%-2% demand growth per annum which prevailed for decades.

According to some anecdotal evidence, if you want 500 MW from Georgia Power, you now have to put up about $600 million upfront. The money will be held against a 10-year power agreement and withdrawn monthly.

Another utility in the south, Alabama Power is making people commit to a minimum 90% of the power requested so they cannot overorder and cancel afterwards.

Bloomberg NEF projects US data center demand will more than double by 2035, rising from 35 GW in 2024 to 78 GW.

The share of total US power used by datacentres could reach 9–12% by 2028–2035, up from around 4% today.

By 2030, AI is projected to drive 35–50% of total datacentre power usage, up from 5–15% in recent years.

The demand is so large it impacts regional electricity prices and infrastructure planning, causing utilities to forecast 75%+ increases in peak electricity loads in data center-heavy regions like Northern Virginia and Texas by 2039.

Higher demand is leading to higher prices will lead to pressure to build more renewable and grid infrastructure. Possible stock names that could benefit from these are NGR, Vistra, NextEra, Southern, Constellation Energy and so on.

US and Europe are power constrained. However, China, Canada, the Middle East and Australia are in a better position, and we are likely to see more datacentres built there.

A Neocloud bubble?

The share prices of the listed neoclouds could indicate a bubble. The chart below shows their performance in the last year. CoreWeave has more than doubled while NebuisNV and IREN has grown more than 5x.

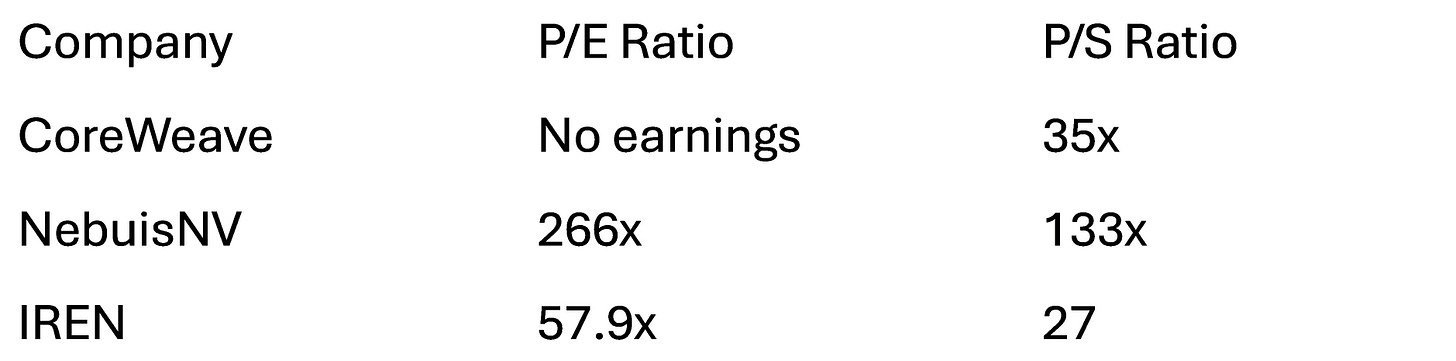

As the table below shows they trade at high valuations .

Perhaps this is evidence of an AI bubble.

Can the neocloud valuations make sense?

If we accept that we are in early stages of a decade-long AI infrastructure buildout. Demand for GPUs, software and networking is going to be strong.

If the rapid growth period continues for 3-5 years, these stocks are likely to prove to be expensive. However, they could face a steep correction if demand growth slows within a year or two, these stocks could prove to be expensive.

These neocloud seem to have appeared out of nowhere or have pivoted from Bitcoin mining (in the case of IREN). It may be that many other similar companies can be funded in which case competition for these companies will only increase. This would be another reason why their current valuation could prove to be too high.

Conclusions

Is there an AI bubble?

This is not an easy question to answer. AI stocks are expensive but so are many other assets.

In our day to day work, we struggle to find stocks which are trading at discounts. I guess we need to look harder!

Gold is up 50% YTD and Cryptocurrencies have also risen strongly in 2025. Perhaps they are also quite expensive relatively to fundamentals – we do not have reliable method to ascertain that.

Bonds are very expensive. Yield spreads of risk bonds relative to safe government bonds are at historically very low levels.

Perhaps there is a bubble in the Neocloud stocks such as CoreWeave and Nebius NV. As noted above they appear to be overvalued.

If the market falls stocks like Nvidia, Microsoft and Arista Networks will fall, perhaps as much as 30% to 40%. Alphabet and Amazon are better relative value, but they too could also perhaps fall as much as 25%.

As equity investors we should always be prepared to face such price declines with equanimity. As Ben Graham famously noted, the market is a voting machine in the short term but a weighing machine in the long run. Mr Market is a moody fellow. We should not be worried.

However, for these quality stocks, we would be inclined to look at large declines with a view to buy more rather than sell in a panic. If the underlying business continues to perform well, these stocks should do well in the long run.

Regardless of whether the AI boom is a bubble or a sustainable revolution, a diversified investment approach is considered the most prudent strategy for managing risk and capturing overall market growth for the vast majority of investors. Betting heavily on a single sector, especially one experiencing rapid, speculative growth, increases portfolio risk.