Micron Technology (MU)

Chips with Everything

About five years ago, before I started this Substack, when I was gainfully employed, I produced a detailed note on semiconductors. It was called “Chips with Everything”. It was the initial work for a potential semiconductor themed actively managed fund on the UBS Asset Management Certificate (AMC) Platform. I learned a lot about the industry from researching and writing the note, but the Fund never saw the light of day.

I can’t help thinking what a great Fund it would have been as Nvidia and ASML were planned to be the largest holdings in a concentrated portfolio.

Ah well, woulda, coulda and shoulda!!.

The 80-page note was seen by a few people, but essentially it disappeared. I found it the other day and re-read it. There was lot of good stories in the things in there- even if I say so myself!! It featured various Noble Prize Winners in Physics; Morris Chang, who was passed over for a job at Texas Instruments and left to later start TSMC; Moore’s Law; The story of the Noyce and others who left Fairchild Semiconductor to found Intel; Jensen Huang of Nvidia and the wonder that is ASML in the Netherlands. Among other companies covered are Broadcom, Marvell and Qualcomm and many others.

I came to appreciate the extraordinary exponential progress the sector has made and how it has completely reshaped entire industries, most of the goods and services we enjoy and how it has enabled many new industries, products and services. The note is a little dated but the historic aspects of it remain relevant. Similar ground is covered by the award-winning book “The Chip War” by Chris Miller published in 2022.

In particular, Miller noted the ubiquity of semiconductors and the scale of their production: “Last year, the chip industry produced more transistors than the combined quantity of all goods produced by all other companies, in all other industries, in all human history.”

The chart below shows the growth of global semiconductor sales which has occurred despite the declines in prices per unit of performance (due to extraordinary rate of technological progress) from around $160bn in 2001 to about $ 580bn in 2022.

If anybody wishes to read the note Chips with Everything, please put your e-mail address in the comments section at the bottom of this article and I will send you a PDF of it.

The major dominant firms of the industry are shown below:

RISC chip design templates - ARM Holdings.

Electronic Design Automation (EDA) - Synopsys, Cadence, Mentor (part of Siemens)

Mainstream Logic Chip players - Nvidia, Intel and AMD

ASIC Custom Chips - Amazon (Graviton), Google (Tensor), Microsoft, Broadcom and Marvell

Memory Chips - DRAM / HBM: Micron Technology, Samsung and SK Hynix - NAND- Micron Technology, Samsung, SK Hynix, Intel, SanDisk and Toshiba

Mobile CPUs - Qualcomm, MediaTek, Samsung, HiSilicon (Huawei), Apple, Samsung

Chip manufacturers - IDMs- Samsung and Intel

Standalone foundries - TSMC, Global Foundries.

Networking - Arista Networks, Cisco, Nvidia (due to takeover of Mellanox), Broadcom, Marvell,

Chipmaking Equipment Manufacturers - ASML, KLA-Tencor, Applied Materials and Lam Research,

Industrial micro-controllers and analogue chips. - Texas Instruments, Analogue Devices, Renesas (Japan).

In addition to these there several Chinese companies such as SMIC, Huawei, Yangtze Memory, and many others

These companies are at the heart of the fast-growing global chip industry and some such as Intel have been around for nearly fifty years.

As NZS Capital puts it in their report on semiconductors “these companies are at the core of a half a trillion-dollar industry that enables us to do pretty much everything, from flying across oceans to booking a ride and ordering a pizza when we get there; from diagnosing and treating a disease to boosting agricultural yields; from supporting the military to powering our cities.”

We have covered some of these companies in these notes reports and will look at others as time allows.

The subject of this Note is Micron Technology (MU).

Introduction

Micron Technology is one of the largest memory chip makers in the world. It makes DRAM (Dynamic Random Access Memory), NAND Flash, and NOR Flash memory, and other memory technologies.

DRAM is the memory used in computers and other devices to store data temporarily while they're running. DRAM is like a memory store where a computer keeps the data it needs to know while it is operating. As tapping into the memory is very fast, all the operations, one does on a computer run smoothly and quickly. DRAM is essential but because it needs constant power to maintain the data, and must be refreshed all the time, it uses more energy and generates more heat compared with other types of memory.

NAND chips are widely used in solid-state drives (SSDs), USB flash drives, digital cameras, smartphones, and other devices where large files are frequently uploaded and replaced.

For the industry, DRAM makes up about 60% of the Memory chip market and NAND is about ~35%. For Micron, DRAM type products account for 66% of the revenue while NAND products account for much of the rest. The customers for these products are in various industries such as mobile, datacentres, consumer, industrial, graphics, automotive, and networking.

Business segments used in financial reporting by Micron are shown below:

The high 43% share for CNBU shows the importance of enterprise, cloud, networks and datacentres.

Micron generates about 55% of its revenue in US with the rest comes from Taiwan, Japan, and other Asia/Pacific region countries. The latter countries feature as their companies make the devices that have embedded memory chips.

Micron has factories (Fabrication plants) and assembly facilities in China, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, and the US. The company makes its own products in a dozen plants globally.

The first thing to say about the chip industry, especially memory chips, is it is highly cyclical. Demand and prices fall sharply and suddenly and companies like Micron can be left with too much inventory which they have to sell at a loss. There are many reasons for this accentuated cyclicality.

The first is macro-economic: Semiconductor sales historical have grown at twice the rate of GDP growth and during a recession, sales fall much more than GDP.

The second factor is the product cycle. If a newly launched product proves to be highly popular, it can lead to huge sudden growth in demand for the memory chips that go into the device.

The third factor is the so-called bullwhip effect. If a company like Dell uses memory chips in its PCs and Servers, they can track the demand in real time, whereas chipmakers like Micron who sit behind them have no such visibility to end-market demand. Therefore, semiconductor companies frequently over-build inventory and face problems if demand for the final product falls.

The chart above shows the cyclicality of the industry. The sharp declines in demand in 2000 after the Dot-com crash, the dislocation and economic uncertainty that followed 9/11 and again after the 2008 global financial crisis, are clearly visible. However overall, the industry has seen a CAGR growth in sales of about 7% over three decades. The blue line shows the progress of the SOX index, which is a basket of semiconductor stocks, which has performed well over the long- term but has seen some long and significant period of corrections and declines.

Chart 1: Annual Revenue and Revenue Growth

Chart 1 above shows Micron annual revenue. The cyclical element is clearly evident. In particular, annual revenue fell from $ 30bn in FY 2022 to ~ $ 15.4 bn in FY 2023.

Chart 2: Quarterly Revenue and Revenue Growth.

Chart 2 above shows quarterly growth and indicates the $ 15bn dip in revenue in 2022/23 involved four or five quarters of lower revenue growth. The company commented on the quarterly trend in their most recent earnings conference call.

“Micron delivered fiscal Q2 revenue, gross margin, and EPS well above the high end of guidance. Micron has returned to profitability and delivered positive operating margin a quarter ahead of expectation.”

“Much improved market conditions, along with the team's excellent execution on pricing, products, and operations, drove the strong financial results. Total fiscal Q2 revenue was $5.8 billion,”

Chart 3: Annual Gross Profit and Operating Profit.

Chart 3 above shows the cyclicality of Gross Profit and Operating Profit. In particular it shows the sharp change from profits in 2022 to losses in 2023. The swing in Gross Profit was $ 19bn.

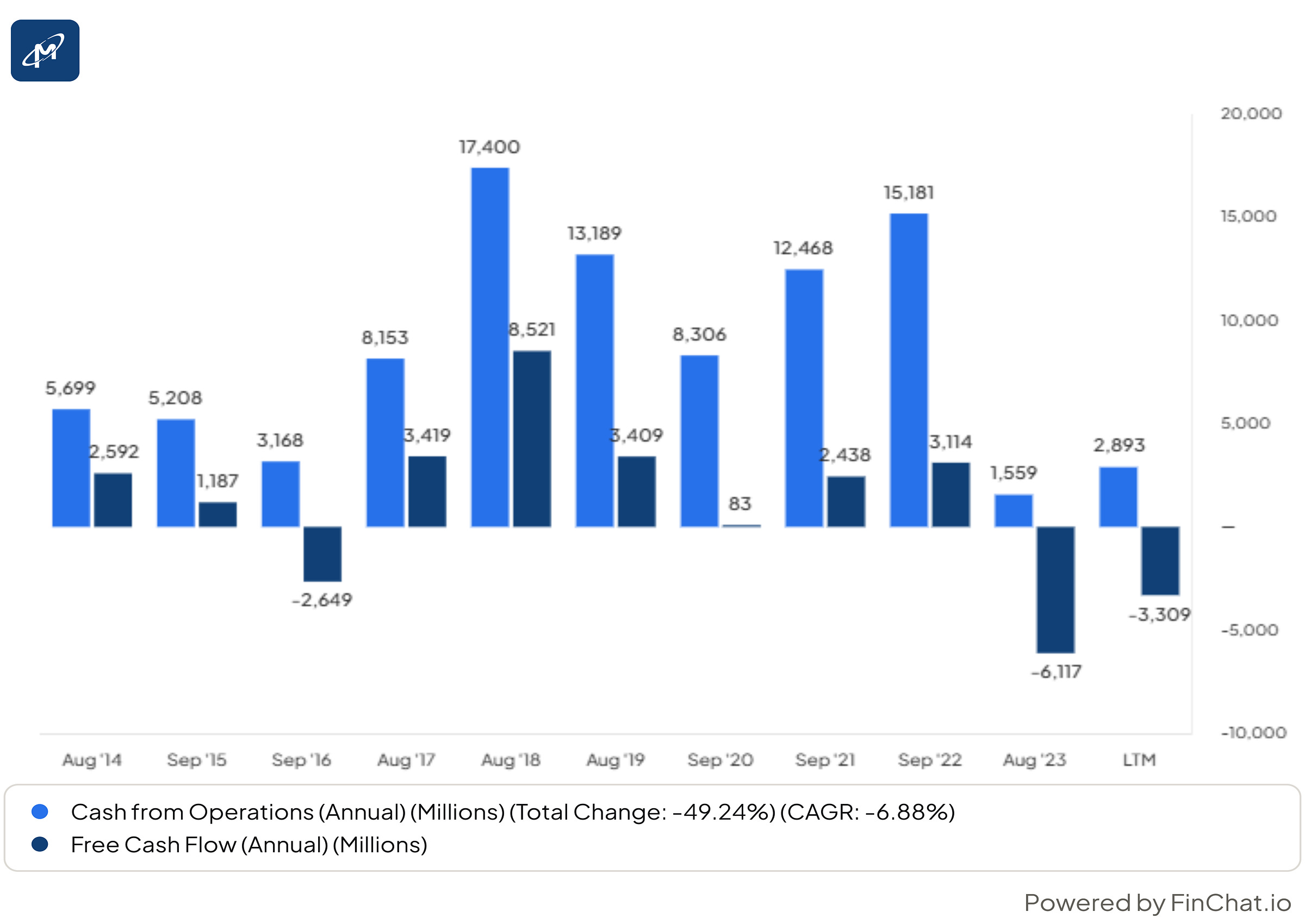

Chart 4: Annual Operating Cash Flow and Free Cash Flow

Chart 4 shows Operating Cash Flow and Free Cash Flow. It indicates the company continued to invest in 2023 despite the significantly reduced operating cash flow. FY2023 Capital Expenditure was about $ 7.7bn compared with $ 12bn in FY 2022 and about $ 10bn in FY 2021. The imperatives of the industry mean that Capital Expenditures cannot be cut beyond a point.

Chart 5: Cash and Long-Term Debt

Chart 5 above shows two balance sheet items: Cash and long-term debt. The company has responded to the negative cash flow numbers by increasing long-term debt rather than running down its cash. The latter fell a little but remained above $ 8bn.

This has changed in the most recent quarter. “On the balance sheet, we held $9.7 billion of cash and investments at quarter end and maintained $12.2 billion of liquidity when including our untapped credit facility. We ended the quarter with $13.7 billion in total debt, low net leverage, and a weighted average maturity on our debt of 2031.”

Chart 6: Interest Coverage and Leverage

Chart 6 shows some of the impact of the significantly higher leverage. Long term debt relative to equity has risen from 0.1 to 0.3. As profits have turned to losses, the EBIT/ interest expense ratio has fallen from 51.4X to -14.1X.

Chart 7: Gross Profit Margin and Operating Profit Margin

Chart 7 above shows the volatility in margins due to the cyclicality in the industry. Both Gross and Operating margins can move significantly as demand and prices change in the cycle.

Chart 8: Return on Equity (ROE) and Return on Capital Employed (ROCE).

The chart above gives some indication of the variability of the profitability of the company.

Chart 9: The number of days of inventory outstanding.

A key statistic for a chip company in the day inventory outstanding. This is an indicative measure of how many days it would take to sell the existing inventory at the current rate of sales. Prima facie the significant rise in inventory days is worrying. The company discussed this issue in their most recent conference call.

“Our fiscal Q2 ending inventory was $8.4 billion or 160 days, roughly in line with the prior quarter. Finished goods were down in the quarter. Our leading-edge supply both for DRAM and NAND is very tight. We expect to reduce inventory levels and excluding strategic inventory stock, be within a few weeks of our 120 days target by the end of fiscal 2024.”

In summary, the financial numbers for Micron show the volatility of the numbers due to the cyclicality of the industry. Although the stock has given great returns, the decision went to invest must take into account the cyclicality of the industry and the company.

Has cyclicality declined over time?

We argue below that cyclicality has reduced over the last two or three decades for logic chips and, to a lesser extent, for memory chips.

We also consider whether the rise of new High Bandwidth Memory (HBM) Chips, which are seeing great demand due to the growth of AI, could further reduce the cyclicality of memory chips.

History

Micron Technology was founded in 1978 far away from Silicon Valley in Boise, Idaho. It started as a semiconductor design firm, but after financial backing from local businessman (who had made their money in potato chips), they started manufacturing silicon memory chips. They built their own production facility in 1980 and sold their first DRAM products in 1982.

Micron went public in 1984. The following year, Japanese chip makers began dumping chips on the US market to capture market share, causing huge losses for US DRAM makers. Micron filed an anti-dumping petition with the International Trade Commission, and in 1986 the US and Japan agreed to a semiconductor trade pact to curb dumping.

The Japanese companies were multi-product conglomerates. They, and their investors, were happy to try to take huge market share in a new sunrise industry, even at the cost of financial losses. For the newly listed Micron, it was a brutal lesson on the cyclical nature of the chip industry, and it was not the last one.

In the last thirty years, Micron has used its cashflow to add capacity or invest in related products to reduce the cyclical exposure.

For example, in the 1990s, Micron expanded into PC manufacturing, in part to soften the impact of the volatile cycles of the memory chip industry. This was not a durable success.

In 1998 Micron bought the memory chip business of Texas Instruments (TI) and with it came plants in Texas, Italy, and Singapore.

In 1999 Micron announced a deal making it the primary supplier of memory chips for PC makers Compaq and Gateway which were major players in that space at the time.

In 1999, Micron also acquired Rendition, a designer of graphics chips, as part of a strategy to enter the logic chip business. Rendition was one of the many GPU companies that lost market share to Nvidia over the years and faded away after a few years.

In 2001, Micron acquired full ownership of Japan-based DRAM maker KMT Semiconductor when it bought out joint venture partner, Kobe Steel. This added DRAM capacity in Japan for Micron.

Also, that year Micron acquired Photobit, a small developer of CMOS image sensors, an image-capturing chip that would become widely used in camera phones and digital still cameras, among other uses. This company was renamed Aptina Imaging. It made Micron the leading supplier of CMOS image sensors in the world; the product line accounted for 11% of Micron’s sales at the peak. Aptina was acquired by On Semiconductor in 2014.

Micron surprised the industry in 2002 by announcing an agreement to buy the DRAM operations of Toshiba. As a result, it was saddled with too much capacity during a very soft DRAM market.

In mid-2006 Micron acquired flash memory maker Lexar Media, an acquisition that bolstered Micron's position in NAND flash memory, The following year, Micron went into solid-state drives based on NAND flash memory with the rollout of its Real SSD product line, The target market was data storage applications (rather than memory) in notebook computers, enterprise computer servers, and data networks. This put Micron into competition with existing players such as Hitachi Global Storage, Seagate Technology, and Western Digital.

The company has also entered the micro-display and solar markets but only the expansion into NAND based SSDs has proved successful.

In summary, Micron has tried to diversify away from memory chips, but these moves have not been successful. They also acquired memory capacity as the industry has consolidated.

The manufacturing process for silicon chips is extremely complex and capital intensive. Historically the speed of inventory obsolescence, particularly for memory chips, is very high.

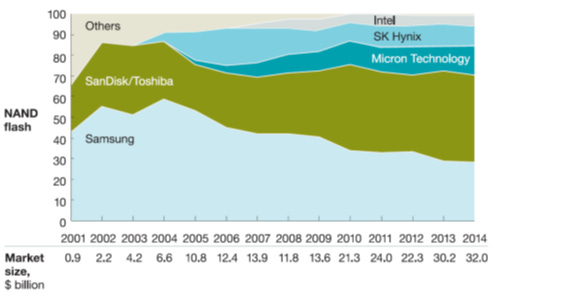

Overall, the industry has done well. Annual demand for NAND and DRAM has grown at an average rate of nearly 26% per annum in the last 30 years. The companies involved have been in a big fight to invest heavily to stay in the game. Over the years, many have pulled out of the memory space, including most Japanese players, Texas Instruments, and others. The cost of R&D budgets and the capital expenditure and the need to be at the cutting edge has led to the disappearance of many suppliers.

Today five players (including Micron) control 94% of the market in NAND and three players (including Micron) control the DRAM market.

The three DRAM producers are Samsung, Hynix and Micron and they control 97% of the market and so have some element of pricing power. The emergence of this DRAM oligopoly is key to understanding the current landscape.

The Chart above shows the market structure in 2008. Elpida Memory, which was the result of the merger of three Japanese companies, went bankrupt in 2012 and was taken over by Micron in 2013. The other companies which controlled about 26% of the market have since disappeared and the DRM industry now essentially consists of just three players, Samsung, SK Hynix and Micron.

Consolidation has also occurred in the logic chip market. Consider the chart below. It shows the number of companies which can make the most advanced chips. In 2002 when the leading-edge node was at 130nm, there were 26 manufacturers that could make logic chips the most advanced chips. By 2019, when the leading edge was at 7nm, it was just three. Today at 3nm it is just TSMC and Samsung. Intel famously failed to make the cut due to engineering problems.

Why are we looking at market structure? In general, the more concentrated a market, the fewer the number of suppliers, the more profitable the industry is likely to be.

One reason is the cost of building a factory to make leading edge chips. As Chris Miller notes in “Chip War”, “a facility to fabricate the advanced logic chips can cost twice as much as an aircraft carrier but may only be cutting-edge for just a couple of years.” Currently the cost of building a facility for the 3nm process node may exceed $20bn.

This reduction in the size of transistors, which means more can be packed on a given size of silicon is an illustration of Moore’s Law. This was the observation made in 1960s that the number transistors in an integrated circuit (IC) doubles about every two years. We discuss this in more detail in the note called “Chips with everything” mentioned above.

Concentration in market structure reduces the negative impact of the cycle. The intensity of price wars declines as the number of suppliers in the market falls.

The logic chip market has become less cyclical. Demand used to be driven by the PC market, more particularly by release of new operating software, such as Microsoft’s Windows 11 Operating System. In recent years, the market has broadened and diversified well beyond PCs to Mobile devices, Cloud datacentre servers, automobile and industrial. These are products which have longer life cycles, and this has helped counter cyclicality and improve profitability.

As NZS Capital states

“For decades, sales revolved around events such as upgrades to the Windows operating system and mobile phone releases. But as the number of use cases and potential profit pools widened due to mega themes such as artificial intelligence, cloud computing, mobility and the Internet of Things, along with expanding industrial and healthcare applications, those cyclical peaks and troughs became less pronounced, making chips even more appealing. …Despite that perception of heightened cyclicality, the profitability of many semiconductor companies now compares with top tier software providers.”

“As the industry has become extremely consolidated over time, the fabs started to accrue and exercise some power over their customers. They were better able to insist on longer term contracts and Non-Cancellable, Non-Returnable (NCNR) elements in the contracts.”

Could this happen in the memory space? The consolidation in the Memory and NAND Industry noted above has helped the profitability of the Micron and SK Hynix, but perhaps, to a lesser extent than has been the case for logic chip companies.

Micron estimates it has the lowest cost curve (of the three oligopolists) in DRAM, while making enormous strides in increasing the proportion of higher margin, differentiated NAND products in their sales mix.

Memory chips are definitely less perishable than they used to be. In the past, quantum leaps in all aspects of memory design and manufacturing permitted massive cost improvements every year: progress was so rapid that if a supplier couldn’t sell inventory in a given quarter, it was virtually worthless in the next because some other supplier offered a superior product at a lower price.

The customer’s survival depended on offering the latest chips in his/her laptop or PC. The DRAM/NAND within (both in terms of price and performance) was a crucial feature. The pace of improvement has slowed down, Moore’s law is reaching the limits of physics.

Experts estimate the current rate of improvement in cost/gigabyte is just 5% p.a. At this rate, suppliers no longer have a desperate need to liquidate inventory at bargain-basement prices – they know they can sell surplus stock at the cost of a small hit to margins.

In DRAM, the three big players are Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron. Samsung is a huge conglomerate which is amongst the most advanced players in logic chip design (along with TSMC). Many of its chips are used for Samsung’s world beating consumer products such as phones and computers. SK Hynix is a pure play memory company. In NAND the same three players feature plus Western Digital and Intel.

How does Micron differentiate itself from these other companies? They believe they have the most advanced DRAM technology, and their NAND portfolio is skewed towards higher value items such as SSD.

“We are ramping the industry’s most advanced DRAM technology into production and have delivered more than 75% of our NAND volume as high-value solutions, supported by record SSD revenue in the quarter. Our portfolio momentum positions us exceedingly well to leverage the long-term growth across our end markets.”

If the structure of the industry has improved and the product-mix of Micron is superior, it should be also reflected in the financial numbers for Micron. It is time for a brief look at the summary numbers for Micron.

Since 1990, the stock has given a respectable return of 15.1% (CAGR) on a total return basis or an overall return of 12,233%. Therefore, it has beaten the return on the S&P 500 over the same period. This shows that a cyclical stock in a growing industry, can be a good long-term investment.

The financial data that we briefly looked at suggests the company has performed well. However, it has suffered at times as demand declines have led to price declines for Memory Chips.

However, recent news suggest that the cycle has turned for Micron. This is reflected in tighter demand and supply situation and higher prices.

“Q2 DRAM revenue was approximately $4.2 billion, representing 71% of total revenue. DRAM revenue increased 21% sequentially, with bit shipments increasing by a low single-digit percentage and prices increasing by high teens.”

“Fiscal Q2 NAND revenue was approximately $1.6 billion, representing 27% of Micron's total revenue. NAND revenue increased 27% sequentially, with bit shipments decreasing by a low single-digit percentage and prices increasing by over 30%.”

Compute and Networking Business Unit revenue was $2.2 billion, up 26% sequentially. Data center revenue grew robustly, and cloud more than doubled sequentially.

Mobile Business Unit was $1.6 billion, up 24% sequentially, as an expected decline in volume was more than offset by improved pricing.

Micron recently announced that it has started mass production of its high-bandwidth memory semiconductors for use in Nvidia's latest chip for artificial intelligence.

Early customers report that the HBM3E (High Bandwidth Memory 3E) consumes 30% less power than rival offerings and indicates that the company will see huge demand for these chips as enterprise, organisations and governments will look to buy chips, that will power generative AI applications.

Nvidia has been using the chip in the H200 graphic processing units and this may continue into the recently announced Blackwell chip. The latter is expected to start shipping in the second quarter and overtake the current H100 chip. SK Hynix is a bigger player in HBM Chips, but Micron seems to have the more power efficient product. In any case, the demand growth is likely to benefit both.

HBMs are the most profitable product for Micron reflecting the technical complexity involved in its construction. Micron is the first company to begin volume production of the HBM3E, a significant first mover advantage over SK Hynix.

Micron has mentioned that early customers report that HBM3E consumes ~30% lower power than the next competitor. Customers can use this to significantly reduce the power consumption in datacentres. As huge new datacentres are being set up all over the world by Cloud Hyperscalers and others, the huge power needs are becoming a huge issue. There are reports of Microsoft and Amazon investing in renewable power assets to address this.

HBM requires twice as much capex as traditional DRAM. Therefore, increasing HBM production will require a lot more capital expenditure.

Micron and the industry are just coming out of a severe downturn and have only just recently stopped burning cash, so they are constrained in the capital expenditure they can do. They must shift whatever cash they generate to HBM capacity. This will reduce industry investment in DRAM and NAND capacity. This is positive as it will reduce price pressures for DRAM and NAND. It will help to reduce the inventory of chips.

The company has noted that HBM production for 2024 and 2025 will be taken up by orders already on hand.

“On HBME, we are sold out for our calendar year '24 supply and calendar year '25 supply is also mostly vast majority is already allocated.”

“HBM carries a higher cost, but it also carries a significantly higher pricing because it brings such great value in the applications in terms of its performance and power. And we are executing well.”

Summary

The Chip industry has been one of the fastest growing and most innovative sectors of the last forty years.

The exponential rise in computing power and the contiguous collapse in price has greatly transformed the whole global economy. It has completely transformed most goods and services and enabled entire new industries.

It has been a cyclical industry, but it has got less cyclical over time, particularly in logic chips. The market structure has become more oligopolistic over time and industry profitability has risen.

Memory markets have been competitive and brutally cyclical in the past, but this has changed over time. The industry has consolidated as the number of players has declined as technology has advanced.

Micron is one of the major players in memory which has gained market share over time.

It is one of just three players in the DRAM market and it focuses on higher value products in NAND.

Its new HBM chips are said to be 30% more power efficient than those of the nearest competitors and they have good demand visibility for HBM production for the next three years at least.

This could herald the beginning of a cyclical upturn for the company for the next two years. The most recent quarterly results suggested that supply is tight, and prices had risen significantly.

Valuation

The rise in earnings is already anticipated on the market. The 2023 EPS was a loss of $ 5.17 per share. The estimate for FY 24 EPS (which ends in September 2024) is expected to $ 0.82 and FY 2025 is expected to be $7.48.

Chart 8: Micron’s fully diluted EPS

As the chart above shows, in profitable years, the EPS has ranged between about $ 2.4 to $ 11.5.

We expect the company to be profitable in the next few years due to higher demand for HBM chips due to investment in AI infrastructure and better supply and demand conditions in the DRAM and NAND products.

“We are in the very early innings of a multi-year growth phase driven by AI as this disruptive technology will transform every aspect of business and society… Memory and storage technologies are key enablers of AI in both training and inference workloads, and Micron is well-positioned to capitalize on these trends in both the data center and the edge.”

The cycle may turn after a few years, so one has to be careful not to value the company on top of the cycle earnings. We do not expect FY 25 net profit and EPS to represent a cyclical top.

Conclusions

All companies have some element of cyclicality in them. In general, we tend to focus on companies which do not have a high degree of vulnerability to the economic cycle. In this sense, Micron is different to the typical stock we consider. If one looks at a metric like P/E ratio for a cyclical stock, the risk is to use a cyclical peak EPS which make the PE ratio look reasonable initially, but subsequently proves to be expensive as the EPS declines.

At the current price of about $124 per share the stock is on a P/E multiple of 16.5 times estimated FY 2025 earnings. Although we expect the higher EPS levels to be maintained or exceeded for a few years more, this valuation may nevertheless be a little too little high.

We have been writing this report while suffering in the heat of Ahmedabad in India. Our productivity has suffered, and it has taken three weeks to write instead of the usual one. This has been expensive delay. In the last two weeks, the Micron share price has risen by about 25% (!)

This makes us reluctant to buy at this price. We have decided to make a token 1% allocation to Micron and hope that the share price falls back to about $ 110 per share which will allow us to add an additional 2% - 3% allocation.

Annexe 1

Extracts from Micron’s most recent earnings conference call

Summary Q2 Results

The quarter was boosted by much higher prices as the market tightened.

“Q2 DRAM revenue was approximately $4.2 billion, representing 71% of total revenue. DRAM revenue increased 21% sequentially, with bit shipments increasing by a low single-digit percentage and prices increasing by high teens.”

“Fiscal Q2 NAND revenue was approximately $1.6 billion, representing 27% of Micron's total revenue. NAND revenue increased 27% sequentially, with bit shipments decreasing by a low single-digit percentage and prices increasing by over 30%.”

Compute and Networking Business Unit revenue was $2.2 billion, up 26% sequentially. Data center revenue grew robustly, and cloud more than doubled sequentially.

Mobile Business Unit was $1.6 billion, up 24% sequentially, as an expected decline in volume was more than offset by improved pricing.

Embedded Business Unit revenue was $1.1 billion, up 7% sequentially on solid demand for leading-edge products in the industrial market.

Storage Business Unit was $905 million, up 39% sequentially with strong double-digit growth across all end markets.

Datacenter SSD revenue more than doubled from a year ago, driven by share gains for Micron's products.

Consolidated gross margin for fiscal Q2 was 20%, up 19 percentage points sequentially driven by higher pricing.

“Capital expenditures were $1.2 billion during the quarter, and free cash flow was near breakeven.

While demand continues to improve, supply is constrained, especially at the leading edge.

More detailed comments

“Micron drove robust price increases, as the supply-demand balance tightened. Improvement was due to a confluence of factors, including strong AI server demand, a healthier demand environment in most end markets, and supply reductions across the industry. AI server demand is driving rapid growth in HBM, DDR5, and data center SSDs, which is tightening leading-edge supply availability for DRAM and NAND. This is resulting in a positive ripple effect on pricing across all memory and storage end markets.”

“We expect DRAM and NAND pricing levels to increase further throughout calendar year 2024 and expect record revenue and much improved profitability now in fiscal year 2025.”

We are at the forefront of ramping the industry's most advanced technology nodes in both DRAM and NAND…over three-quarters of our DRAM bits are now on leading-edge 1-alpha and 1-beta nodes, and over 90% of our NAND bits are on 176-layer and 232-layer nodes.

“We have matured our production capability with extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography and have achieved equivalent yield and quality on our 1-alpha as well as 1-beta nodes between EUV and non-EUV flows.”

“We have begun 1-gamma DRAM pilot production using EUV and are on track for volume production in calendar 2025. The development of our next-generation NAND node is on track, with volume production planned for calendar 2025. We expect to maintain our technology leadership in NAND.”

“Inventories for memory and storage have improved significantly in the data center, and we continue to expect normalization in the first half of calendar 2024. “

“We are in the very early innings of a multiyear growth phase driven by AI as this disruptive technology will transform every aspect of business and society… Memory and storage technologies are key enablers of AI in both training and inference workloads, and Micron is well-positioned to capitalize on these trends in both the data center and the edge.”

“Micron will be the biggest beneficiaries in the semiconductor industry of this multiyear growth opportunity driven by AI. In data center, total industry server unit shipments are expected to grow mid to high single digits in calendar 2024, driven by strong growth for AI servers and a return to modest growth for traditional servers. Micron is well positioned with our portfolio of HBM, D5, LP5, high-capacity DIMM, CXL, and data center SSD products.”

“Improved memory bandwidth, power consumption, and overall performance is critical to enable cost-efficient scaling of AI workloads inside modern GPU or ASIC-accelerated AI servers.”

“Blackwell GPU architecture-based AI systems, require a 33% increase in the HBM3E content, continuing a trend of steadily increasing HBM content per GPU. Micron's industry-leading high-bandwidth memory HBM3E solution provides more than 20 times the memory bandwidth compared to standard D5-based DIMM server module.”

“(We have) strong feedback that our HBM3E solution has a 30% lower power consumption compared to competitors' solutions.”

“We have a robust roadmap, and we are confident we will maintain our technology leadership with HBM4, the next generation HBM, which will provide further performance.”

“We expect AI phones to carry 50% to 100% greater DRAM content compared to non-AI flagship phones today. Micron's leading mobile solutions provide the critical high performance and power efficiency needed to unlock an unprecedented level of AI capability.”

“Our mobile DRAM and NAND solutions are now widely adopted in industry-leading flagship smartphones, with two examples being Samsung's Galaxy S24 and the Honor Magic 6 Pro announced this year. The Samsung Galaxy S24 can provide two-way, real-time voice and text translations during live phone calls. The Honor Magic 6 Pro features the Magic LM, a seven-billion parameter large language model, which can intelligently understand a user's intent based on language, image, eye movement, and gestures and proactively offer services to enhance and simplify the user experience”.

“Industry supply-demand balance is tight for DRAM and NAND, and our outlook for pricing has increased for calendar 2024. Over the medium term, we expect bit demand growth CAGRs of mid-teens in DRAM and low-20s percentage range in NAND. Turning to supply. Supply outlook remains roughly the same as last quarter. 2024 industry supply to be below demand for both DRAM and NAND.”

Micron's fiscal 2024 CapEx plan remains unchanged at a range between $7.5 billion and $8.0 billion.

“Micron's capital-efficient approach to reuse equipment from older nodes to support conversions to leading-edge nodes has resulted in a material structural reduction of our DRAM and NAND wafer capacities. We believe this approach to node migration and consequent wafer capacity reduction is an industry-wide phenomenon.”

“Significant supply reductions across the industry have enabled the pricing recovery that is now underway. Although our financial performance has improved, our current profitability levels are still well below our long-term targets, and significantly improved profitability is required to support the R&D and CapEx investments needed for long-term innovation and supply growth.”

“Ramp of HBM production will constrain supply growth in non-HBM products. Industrywide, HBM3E consumes approximately three times the wafer supply as D5 to produce a given number of bits in the same technology node. we expect the trade ratio for HBM4 to be even higher than the trade ratio for HBM3E. We anticipate strong HBM demand due to AI, combined with increasing silicon intensity of the HBM roadmap, to contribute to tight supply conditions for DRAM across all the end markets.”

“HBM3E needs three times more wafers than DDR5 in the same technology … So this is of course highly silicon intensive technology and this factor of three has the trade ratio between HBM and D5 is really common across the industry.”

“HBM is in a high-demand growth phase and this demand growth will continue in terms of bits, in terms of revenue over the course of the foreseeable future. And this is putting tremendous pressure on the non-HBM supply. The trade ratio of three to one, increasing demand in HBM, increasing -- increased profitability of HBM is putting non-HBM part of the memory in tight supply.”

“Vast majority of our production supply is allocated, and some of the pricing is already firmed up. Keep in mind, this has never happened before. And that resulted in a structural reduction in wafer capacity in the industry as well. And then there is the HBM factor. This overall tight supply environment bodes well for our ability to manage the pricing increases as well as keep an eye on demand-supply balance and remain extremely disciplined in driving the growth of our business in revenue and profits while continuing to execute our strategy of maintaining stable bit share. So leading edge is very tight, and we are continuing to work on maximizing our output, which means leading edge is running at full utilization at this point.”

“We are totally focused on increasing our production capability -- for HBM to be in line with our DRAM share.

Annexe 2

Political Risk

The sector has large elements of political risk. We will briefly discuss two elements of this.

Although, the US semiconductor industry accounts for almost half of global semiconductor revenue, the share of semiconductor manufacturing capacity in the US has declined from 37% in early 2000s to just 12% of global production.

Taiwan in general and TSMC in particular makes about 40% of advanced chips. Taiwan is seen as rogue state by the Peoples’ Republic of China and the latter has a stated aim of capturing it. Such an event would be catastrophic for the world economy if chip manufacturing capacity was disrupted or damaged. Micron has plants in Taiwan as well as in Brunei, Penang (Malaysia) and Singapore.

Chris Millar in “The Chip War” put it as follows:

“After a disaster in Taiwan, in other words, the total costs would be measured in the trillions. Losing 37 percent of our production of computing power each year could well be more costly than the COVID pandemic and its economically disastrous lockdowns. It would take at least half a decade to rebuild the lost chipmaking capacity. These days, when we look five years out, we hope to be building 5G networks and metaverses, but if Taiwan were taken offline we might find ourselves struggling to acquire dishwashers.”

Another, related political risk concerns China’s dependence on US designed chips. China is the largest global manufacturer of products and devices that use chips. Following allegations of IP theft and general heightened political risk and trade wars, both the Trump and Biden administration have raised tariffs and banned the exports of the more advanced chips to Chinese companies. This has an impact of demand. The Biden administration forbade Nvidia from selling its most advanced chips to China. In its most recent quarterly results, Nvidia noted the China was one of the few markets where they saw a sales decline. In the event, demand was so strong elsewhere, it did not prevent them for delivering record results.

The inherent vulnerability for China has led to a policy change to become a global high-tech powerhouse and aspirations for high-tech manufacturing and advanced technologies. China aims to achieve a self-sufficiency rate of forty percent for semiconductors of seventy percent by 2025. Today, roughly 16 percent of semiconductors used in China are produced in-country. There are some questions as to the progress achieved on this, but it clearly threatens the US aim to achieve pre-eminence in technology. From Micron’s point of view, the main threat is Yangtze Memory Company which is China’s leading memory chip manufacturer.

There are some difficult issues here which cannot consider in detail here. The US cannot dictate its lead in technology while embracing free market capitalism. China cannot enter a global market economy under WTO rules by ignoring IP rights as well as providing hidden subsidies to its companies.

Thank you. I would like to get a pdf copy as well <tsim0206@gmail.com>.

krajcz@wp.pl

Thank you very much, appreciate your work!